Paragraph 8

Where the roles of the general government are primarily limited to;

a) Providing defense, and controlling our borders,

b) Representing external relations for the Union and act as a Nation to those people outside Our County,

c) Taking its direction from the representatives of the Sovereign States, and not interfere or hamper in their decisions,

d) Helping unhamper interstate commerce and settle differences between the States, and most importantly,

e) Establishing a standard for money, which will help ensure honest communication between all Peoples,

Article I Section 8, which is copied below, enumerates the limited powers of the general government. Well, at least that was the plan anyway. The general government was only and should still only (if the oath means anything) have few powers that are general in nature. Nothing makes the Federal Government superior to the states, there is only the granting of a few general powers. Those not enumerated are left to the States or the people, which is our 10th Amendments. It’s pretty clear that what we have today regarding powers has gone well beyond what was envisioned, and to our detriment. It’s not sustainable.

There are many reasons for the large expansion of powers and resulting big government, some of which will be explained in this website. The states are very responsible for giving up their power. And. they need to take it back. The War For Southern Independence (Civil War) helped usher in big government. This will be discussed elsewhere in this website. Also, when Supreme Court gave the general government the power of the printing press, which is one area where I have focused on explaining in this website, it allows for this enormous expansion of government. What I have written above in “I’m an American” are general powers where I believe we should concentrate our energies on as the mess or debacle we are about to enter begins.

Some people will say the Federal Government is sovereign and

that the state government gave up their sovereignty to it. If it’s sovereign

it can make any laws it believes are necessary and proper. Nothing could

be further from the truth! Justice Fields provides an explanation regarding this type of thinking in Juilliard v. Greenman, “. . . . But be that as it may, there is no such thing as a power of inherent sovereignty in the government of the United States. It is a government of delegated powers, supreme within it’s prescribed sphere, but powerless outside of it. In this country sovereignty resides in the people, and Congress can exercise no power which they have not, by their Constitution, entrusted to it; all else is withheld. . . . If a power is not in terms granted, and is not necessary and proper for the exercise of a power which thus granted, it does not exist…….” (Juilliard v. Greenman is provided in the dropdown Menu above Prove It, Paragraphs 17-22, page 467)

Some will accuse me of being naive or unrealistic. Something must be

done and at least I offer a guide to fixing the problem. Education

about how our system should work and was intended to work is vitally

important if we are to keep our Republic. Going on about business as

usual unfortunately is not an option at the present time.

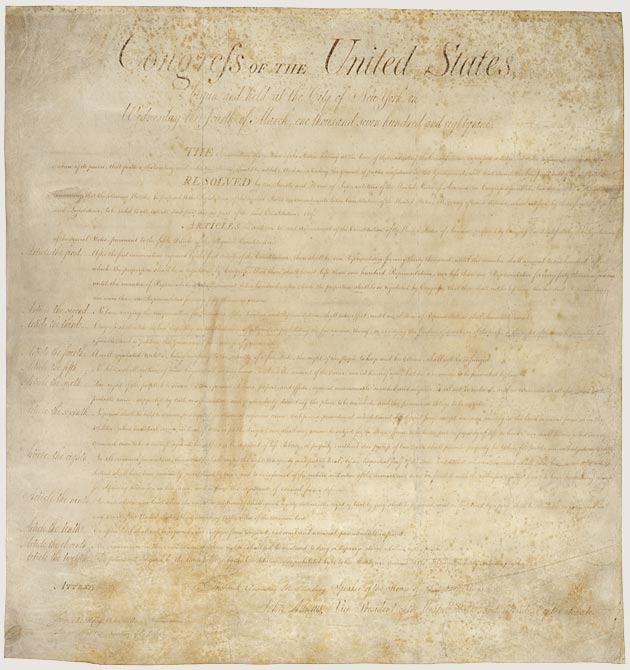

ARTICLE I, SECTION 8 OF THE CONSTITUTION FOLLOWS:

The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States; but all Duties, Imposts and Excises shall be uniform throughout the United States;

- To borrow Money on the credit of the United States;

- To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes;

- To establish an uniform Rule of Naturalization, and uniform Laws on the subject of Bankruptcies throughout the United States;

- To coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin, and fix the Standard of Weights and Measures;

- To provide for the Punishment of counterfeiting the Securities and current Coin of the United States;

- To establish Post Offices and post Roads;

- To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries;

- To constitute Tribunals inferior to the supreme Court;

- To define and punish Piracies and Felonies committed on the high Seas, and Offences against the Law of Nations;

- To declare War, grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal, and make Rules concerning Captures on Land and Water;

- To raise and support Armies, but no Appropriation of Money to that Use shall be for a longer Term than two Years;

- To provide and maintain a Navy;

- To make Rules for the Government and Regulation of the land and naval Forces;

- To provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions;

- To provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining, the Militia, and for governing such Part of them as may be employed in the Service of the United States, reserving to the States respectively, the Appointment of the Officers, and the Authority of training the Militia according to the discipline prescribed by Congress;

- To exercise exclusive Legislation in all Cases whatsoever, over such District (not exceeding ten Miles square) as may, by Cession of particular States, and the Acceptance of Congress, become the Seat of the Government of the United States, and to exercise like Authority over all Places purchased by the Consent of the Legislature of the State in which the Same shall be, for the Erection of Forts, Magazines, Arsenals, dock-Yards, and other needful Buildings;—And

- To make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.

Some will argue that where the Constitution states in the beginning of Article I Section 8, “…and general welfare” and that this gives the Congress the power to do just about anything to promote the general welfare of the country. This was a concern, too, at the founding. James Madison addressed this concern in Federalist No. 41. He assured the public that, “ Nothing is more natural nor common than first to use a general phrase, and then to explain and qualify it by a recital of particulars. ” He was explaining that this “general welfare” wording was then followed by the enumerated powers. No other powers were given. He explained to those concerned how one uses the English Language to express thoughts. I copy the relevant parts of Federalist No. 41 below.

From Federalist No. 41, excerpt

. . . . Some, who have not denied the necessity of the power of taxation, have grounded a very fierce attack against the Constitution, on the language in which it is defined. It has been urged and echoed, that the power “to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises, to pay the debts, and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States,” amounts to an unlimited commission to exercise every power which may be alleged to be necessary for the common defense or general welfare. No stronger proof could be given of the distress under which these writers labor for objections, than their stooping to such a misconstruction. Had no other enumeration or definition of the powers of the Congress been found in the Constitution, than the general expressions just cited, the authors of the objection might have had some color for it; though it would have been difficult to find a reason for so awkward a form of describing an authority to legislate in all possible cases. A power to destroy the freedom of the press, the trial by jury, or even to regulate the course of descents, or the forms of conveyances, must be very singularly expressed by the terms “to raise money for the general welfare. ” But what color can the objection have, when a specification of the objects alluded to by these general terms immediately follows, and is not even separated by a longer pause than a semicolon? If the different parts of the same instrument ought to be so expounded, as to give meaning to every part which will bear it, shall one part of the same sentence be excluded altogether from a share in the meaning; and shall the more doubtful and indefinite terms be retained in their full extent, and the clear and precise expressions be denied any signification whatsoever? For what purpose could the enumeration of particular powers be inserted, if these and all others were meant to be included in the preceding general power? Nothing is more natural nor common than first to use a general phrase, and then to explain and qualify it by a recital of particulars. But the idea of an enumeration of particulars which neither explain nor qualify the general meaning, and can have no other effect than to confound and mislead, is an absurdity, which, as we are reduced to the dilemma of charging either on the authors of the objection or on the authors of the Constitution, we must take the liberty of supposing, had not its origin with the latter. The objection here is the more extraordinary, as it appears that the language used by the convention is a copy from the articles of Confederation. The objects of the Union among the States, as described in article third, are “their common defense, security of their liberties, and mutual and general welfare. ” The terms of article eighth are still more identical: “All charges of war and all other expenses that shall be incurred for the common defense or general welfare, and allowed by the United States in Congress, shall be defrayed out of a common treasury,” etc. A similar language again occurs in article ninth. Construe either of these articles by the rules which would justify the construction put on the new Constitution, and they vest in the existing Congress a power to legislate in all cases whatsoever.

But what would have been thought of that assembly, if, attaching themselves to these general expressions, and disregarding the specifications which ascertain and limit their import, they had exercised an unlimited power of providing for the common defense and general welfare? I appeal to the objectors themselves, whether they would in that case have employed the same reasoning in justification of Congress as they now make use of against the convention. How difficult it is for error to escape its own condemnation!

PUBLIUS.

“. . . . But what color can the objection have, when a specification of the objects alluded to by these general terms immediately follows, and is not even separated by a longer pause than a semicolon?”

“. . . . Nothing is more natural nor common than first to use a general phrase, and then to explain and qualify it by a recital of particulars.”